6.3 The Transaction of Forces

“There is no ‘action at a distance’ in the universe, nor invisible ropes. What we call ‘force’ is merely a transfer transaction that two vectors perform to rebalance their respective budget sheets when they meet.”

In the previous two sections, we constructed a static picture of particles: each particle is an independent “origami work,” rotating alone in its own internal geometric dimensions. However, if the universe were just countless non-interfering tops, it would be an extremely boring world.

For galaxies to condense, atoms to combine, and us to perceive each other, these independent vectors must become correlated.

In classical physics, this correlation is called “Force”. Newton told us that force is push and pull between objects; field theory tells us that force is coupling between fields. But from the economic perspective of Vector Cosmology, force is neither push-pull nor coupling; it is a naked “Budget Transaction”.

Interaction is essentially the transfer mechanism in the universe.

Sector Collision: When Circles Meet

Imagine two vectors evolving independently in projective Hilbert space—say, an electron and a proton. As long as they are far apart, they remain safe under their respective budget constraints.

But when they approach each other in space (wave functions overlap), a geometric Basis Rotation occurs.

Mathematically, the total Hilbert space of two interacting systems is a tensor product structure . The existence of the interaction term means that the original “private accounts” are no longer closed. The system’s evolution trajectory no longer depends solely on their respective internal states but on the combination of both states.

This is like two originally independent rotating gears suddenly meshing together. One gear’s rotation () will forcibly drive the other gear’s rotation or force the other gear to change its rotation speed.

This “rotation speed change caused by geometric meshing” is what we macroscopically feel as “force.”

Feynman Diagrams: The Universe’s Transaction Ledger

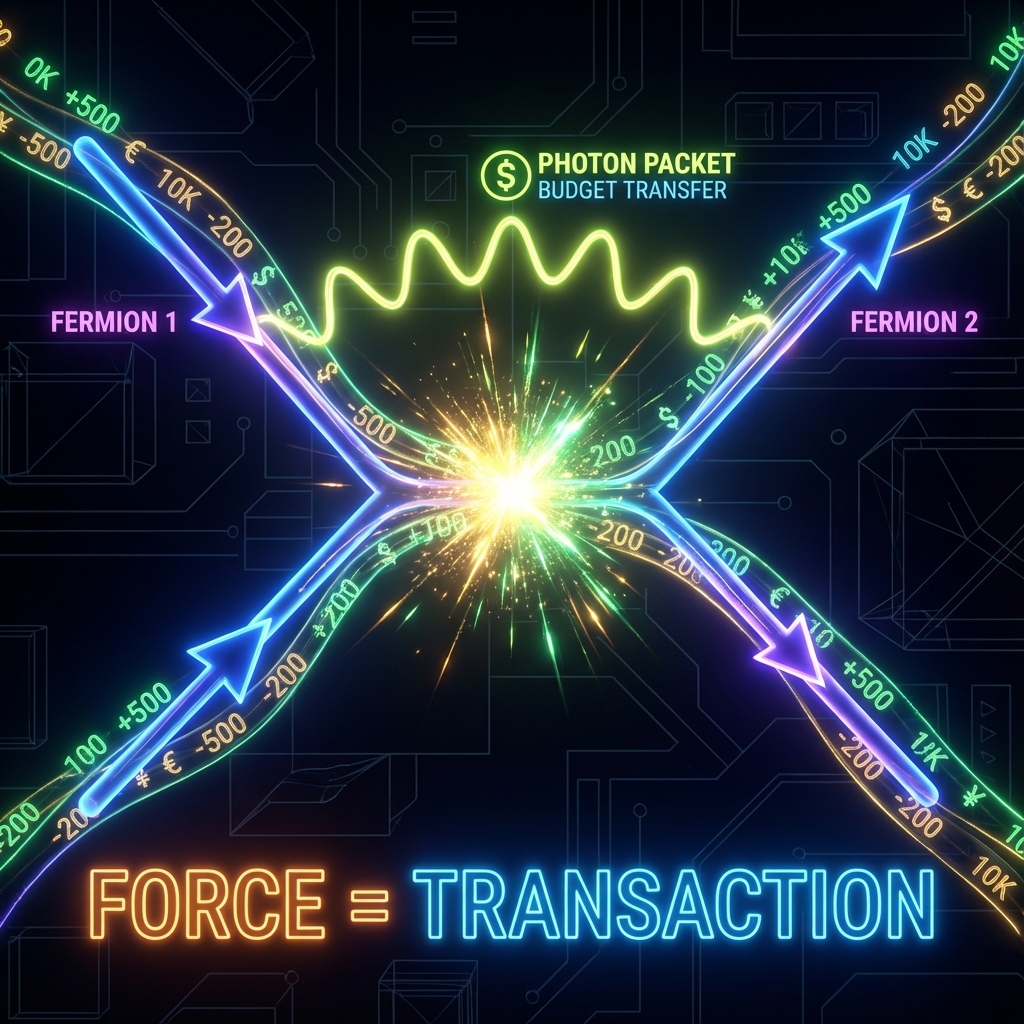

To vividly describe this transaction, physicist Richard Feynman invented the famous Feynman Diagrams. Usually, we view them as path diagrams of particle collisions. But in our framework, each Feynman diagram is actually an accounting voucher.

Let us look at the simplest transaction case: electron emitting a photon.

-

Before transaction:

An electron moves in space. It has certain (kinetic energy) and enormous (mass). Its total budget is balanced.

-

Transaction point (Vertex):

The vertex on the Feynman diagram is the moment the transaction occurs.

The electron decides to “purchase” an orbital change (acceleration or deceleration). To pay for this expense, it must surrender part of its budget.

It cannot surrender mass (that is fixed assets locked by the Higgs mechanism), but it can surrender kinetic energy (part of ) or high-energy internal excited states.

-

After transaction:

The electron’s velocity changes (recoil occurs). Where did that surrendered budget go?

It is packaged into a new package—photon.

Photon is a pure carrier. It takes away the share paid by the electron and flies at light speed into the depths of the universe until it meets the next trader.

In this process, no new energy is created. The budget is merely transferred from the electron’s account () to the photon’s account (). The so-called “electromagnetic force” is the momentum recoil produced by constantly throwing and receiving these “budget packages.”

The Economics of Force: Payment and Recoil

This perspective perfectly explains the essential characteristics of force:

-

Repulsion:

Two electrons approach each other. They are like two skaters on ice, throwing heavy money bags (virtual photons) at each other.

A throws money bag A gains reverse momentum (moves back).

B catches money bag B gains forward momentum (moves back).

Result: They move away from each other. They are not “pushing” each other; they are just performing high-frequency momentum transactions.

-

Attraction:

This is a more complex “borrowing” transaction.

In quantum field theory, attraction usually involves coherent superposition of wave functions, causing energy density reduction in the intermediate region.

In vector economics, this is similar to two companies merging assets. Positive and negative charges, by exchanging photons, are actually sharing part of the internal budget. This sharing reduces the system’s total energy level (total requirement), making “combining” a more cost-effective state than “separating” (more favorable entropy increase or lower energy).

Coupling Constants: The Universe’s Exchange Rate

Why is the strong force stronger than the electromagnetic force? Why is gravity so weak?

In the Standard Model, this is determined by Coupling Constants (such as the fine structure constant ).

In FS geometry, coupling constants are Exchange Rates.

-

Strong force exchange rate: Extremely high. This means transactions in the sector (color charge) can be extremely efficiently converted to (kinetic energy). A tiny change in color charge can trigger enormous energy bursts (like nuclear force).

-

Gravitational exchange rate: Extremely low. Gravity is the currency with the worst exchange rate in the universe. You need to accumulate astronomical amounts of mass assets () to exchange for a tiny weak curvature effect in external space ().

Virtual Particles: Usury and Credit Overdraft

Finally, we must explain a strange phenomenon: Virtual Particles. In quantum mechanics, particles seem to borrow energy out of thin air, as long as they pay back fast enough (Heisenberg uncertainty principle ).

This is the universe bank’s Overdraft mechanism.

FS capacity is strictly conserved, but this only applies to Real Particles. On extremely short time scales, geometric structure allows budget blurring. An electron can briefly “borrow” budget exceeding , emitting an overweight virtual boson, as long as this boson disappears (is absorbed) before the universe’s auditor (decoherence or long-time observation) arrives.

Force propagation often relies on this instantaneous, rule-breaking usury transaction. And the force’s range depends on how long this loan can be delayed (the larger the virtual particle’s mass, the shorter the repayment period, the shorter the range).

Chapter Summary

Force is not magic; force is transaction.

The entire universe is like a busy stock exchange. Feynman diagrams are transaction records, bosons are checks, fermions are investors, and coupling constants are the day’s exchange rates.

Everything can connect through “force” because they share the same fund pool—. Every physical action, whether atomic breathing or galactic collision, is a series of transfers, loans, and settlements in this huge fund pool.

Now that we understand how particles form structures through “transactions,” the next question is: Where are the total accounts of these transactions—that is, the universe’s macroscopic history—recorded?

This leads to the most mysterious chapter of this book. We will reveal that all transaction records, all physical constants, and even all particle types may have been encoded in the simplest mathematical constant. Next chapter: The Holographic Code of .