5.3 Distinguishing Reality from Noise

“Truth is often obscured by noise, but geometry has eyes that penetrate the fog. We must learn to distinguish: which part is the skeleton of the universe, and which part is merely dust on the lens.”

In the previous section, we painted an exciting prospect: through quantum walk experiments, we can observe the “droop” of the relativistic circle at the microscopic limit, thereby directly seeing the discrete nature of spacetime. However, any rigorous experimental physicist would raise a sharp question at this point:

“Is the ‘droop’ you see really from spacetime’s lattice structure, or is it merely because your instruments are imperfect?”

This question strikes at the core. In the real world, no system is a perfect closed system. Laboratories are full of thermal fluctuations, laser instabilities, and quantum decoherence. These factors all cause the system to lose information.

The Pythagorean identity we established in Volume 1 must include that forgotten third term—environment sector ()—in real environments:

Even if spacetime were a perfect continuum (no lattice droop), as long as environmental noise exists (), the value on the left side of the equation would also be less than . That is, noise also causes data points to fall inside the circle.

If both noise and lattice effects cause “circle shrinkage,” how do we distinguish which one is the truth of the universe and which one is experimental error?

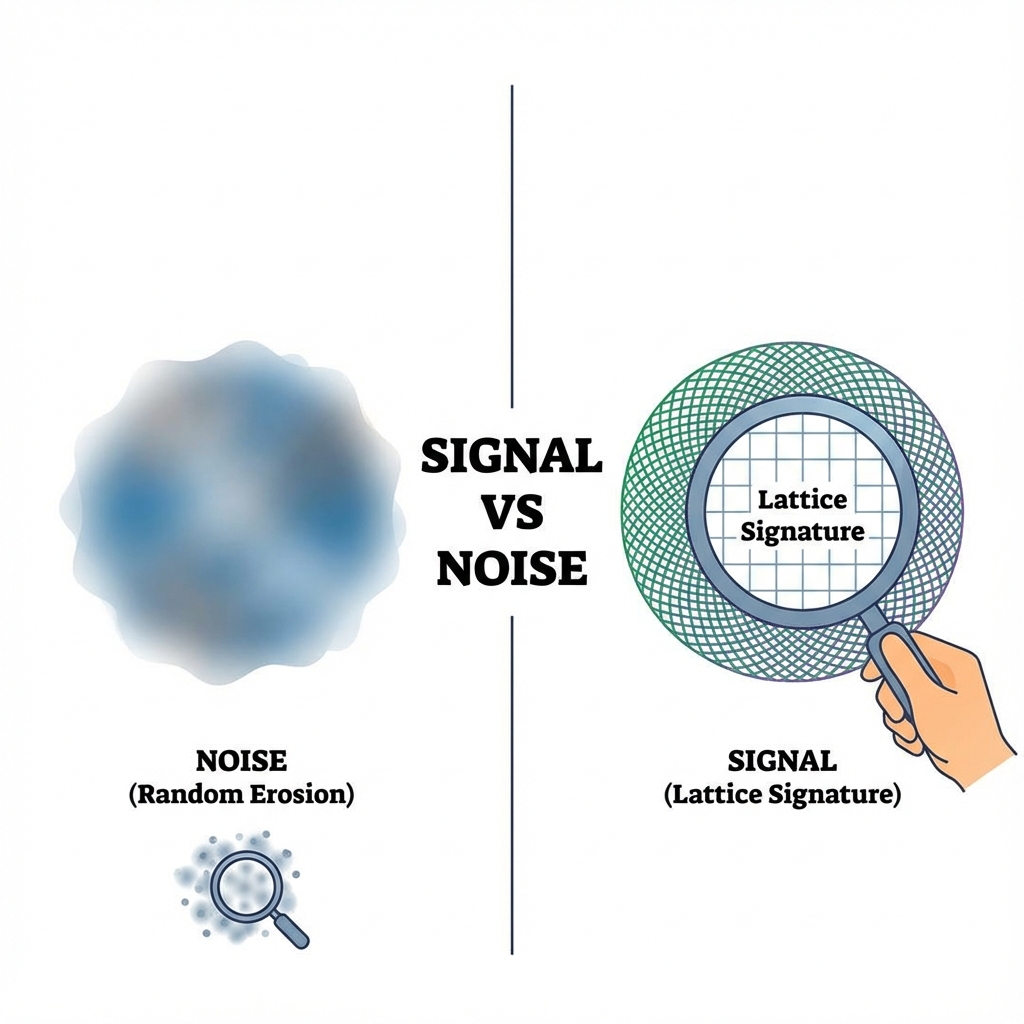

Geometric Fingerprints: Determinism vs. Randomness

Fortunately, in the framework of Vector Cosmology, these two have completely different “geometric fingerprints”.

-

Noise’s fingerprint: uniform erosion

Environmental noise (such as depolarizing channels) is usually a statistical random process. It is like an omnipresent friction, indiscriminately devouring the system’s coherence.

In experimental charts, noise-induced circle shrinkage usually has little relationship with momentum (), or shows a uniform decay proportional to the number of time steps. It manifests as overall shrinkage of the circle radius, like a deflating balloon.

-

Lattice’s fingerprint: specific deformation

In contrast, lattice droop is not random; it is a deterministic geometric effect. It originates from the mathematical structure of the dispersion relation .

This effect has extremely strong momentum dependence:

-

In the low-momentum region (), lattice effects are almost zero, and the circle remains perfect.

-

In the high-momentum region (), lattice effects increase exponentially and dramatically.

This is not just a balloon getting smaller; this is the balloon’s shape undergoing specific distortion.

-

The Inequality of Truth

To capture this weak signal in noise-filled reality, we derived a quantitative criterion.

Let us define two quantities:

-

: Theoretical deviation (droop amount) caused by lattice structure. This depends entirely on your momentum setting.

-

: Deviation caused by environmental noise. Here is the error probability of each operation, and is a coefficient.

On the information-velocity circle chart, noise delineates a “Forbidden Zone”—the gray shaded region in the figure. Any data point falling in this region cannot be distinguished from simple instrument error.

Only when the magnitude of lattice droop is much greater than the noise level can we be confident that we are seeing spacetime’s skeleton. This gives the golden inequality for experimental success:

This means that to “see” the universe’s pixels, we don’t need to eliminate noise infinitely; we only need to push the experiment into the high-momentum region (). There, the deformation caused by discrete geometry will become so dramatic that no random noise can mimic it.

Distinguishing “Pixels” from “Dust”

This criterion has profound philosophical significance.

When we observe the world through a microscope, we see blurry spots.

-

If these spots jump randomly, that is dust on the lens (environmental noise ).

-

If these spots are arranged in a neat grid and show regular moiré patterns as we change our viewing angle, that is the pixels of the film (lattice geometry).

Vector Cosmology tells us that we need not fear noise. As long as we master the correct geometric language (FS metric), we can extract that deterministic drooping curve belonging to the universe’s underlying structure from noisy experimental data.

That curve is not error; it is the signature of discrete spacetime. It proves that at that extreme scale, that perfect circle ruling the macroscopic world finally has to bow to the iron law of finiteness.

At this point, we have completed the disassembly of the universe’s microscopic engine. We have confirmed that it is discrete, finite, and traceable.

But how does this machine made of pixels weave the colorful, full-of-things world we see? How do those simple “bits” and “grids” combine into electrons, quarks, and even you and me?

To answer this question, we need to enter the next volume. We will leave the underlying engine room and come to the upper origami workshop. There, we will witness how a single vector gives birth to all things through complex recursive folding.