10.1 The Observer’s Trap

If force is geometric slope, and objects always slide toward lowest energy, then for conscious observers, where is this “lowest point”?

We usually think life pursues excellence. Evolution tells us survival of the fittest; human history seems an epic of constant upward climbing. But if we honestly examine our surroundings, even our own hearts, we find another, stronger force: inertia.

Most people, most of the time, are not “climbing.” We repeat. We do the same work day after day, scroll the same phone, hold the same views. Changing lifestyle, breaking mental patterns is so difficult that we often only try to change after suffering major blows (external perturbations).

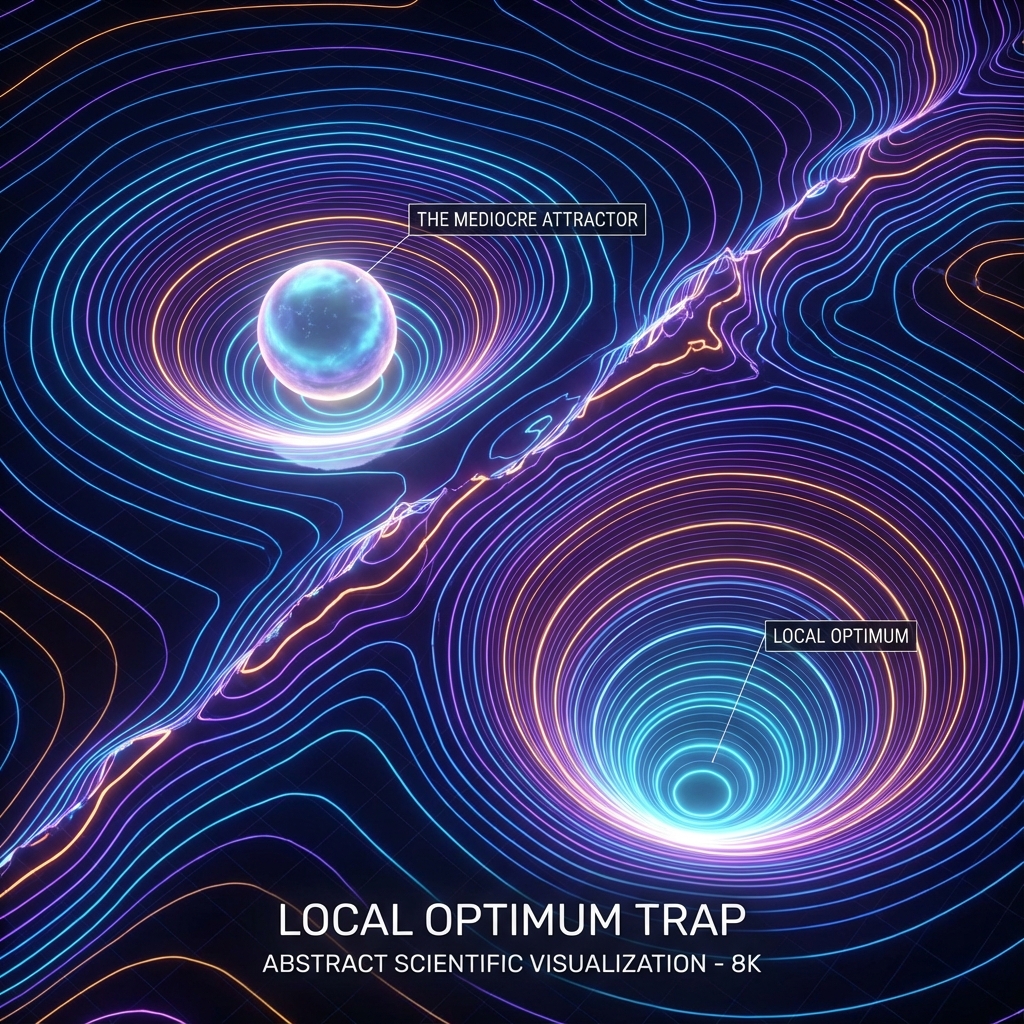

In psychology, this is called the “comfort zone.” But in our geometric reconstruction, it has a more precise, colder name: The Mediocre Attractor.

Valleys in Strategy Space

Let us imagine an observer as a point in Hilbert Space. This point doesn’t just represent your physical location; it represents your entire state—your memories, beliefs, behavioral patterns. We call the set of all possible states Strategy Space.

In this multidimensional space, terrain is not flat.

According to the “universal formula of force” we established in Chapter 9, , observers always tend to evolve toward directions of “least resistance.”

What is least resistance? For a bandwidth-limited ( finite) computational system, least resistance means lowest computational cost.

-

Thinking is expensive: Re-evaluating a belief, or learning a new skill, requires mobilizing vast internal evolution rate . This consumes energy, produces heat (anxiety).

-

Habits are cheap: Using existing neural circuits, living today according to yesterday’s patterns, requires almost no extra computational resources.

Therefore, in strategy space, those highly repetitive, thoughtless automatic behavioral patterns form huge geometric depressions, valleys of potential energy.

Once an observer’s trajectory slides into this valley, according to geometric mechanics, without strong external force, they will struggle to climb out. They will begin circling at the bottom, forming a closed loop.

This is an “attractor.” It is the destination in dynamical systems, where all trajectories ultimately converge.

The Geometric Essence of Mediocrity

Why do we call it “mediocre”?

There is no moral criticism here. Geometrically, “mediocre” means local optimum (Local Optimum).

In this depression, everything is self-consistent. Your views explain the world you see; your actions bring expected feedback. In this small closed loop, (distance between reality and expectation) is minimized. You feel comfortable, safe, at ease.

But this is only a local deep well.

Beyond the well mouth, farther in strategy space, there may exist a deeper, broader, more self-consistent “valley of truth.” This is the “true self orbit” we will discuss in Chapter 11.

However, a high potential barrier separates them.

To cross this barrier, observers must first do something counterintuitive: actively increase . That is, actively embrace confusion, pain, and uncertainty. This is extremely expensive energetically.

For a physical system following the “principle of least action,” unless extra energy is injected, it will never actively cross barriers. It will be forever trapped in that shallow pit until thermodynamics’ end.

This is why “change” is so difficult. Not because you lack willpower, but because the universe’s fundamental geometric structure opposes you. You are fighting the same law governing quarks and galaxies—the principle of energy minimization.

The Curse of Dimensionality

Worse, this trap is often dug by observers themselves.

In Chapter 7, we mentioned that observers are “lossy compression” projection mechanisms. To save bandwidth, we ignore information irrelevant to our needs. We label the complex world with simple tags.

This simplification actually reduces strategy space’s dimensionality.

When we project infinite-dimensional reality onto low-dimensional cognitive models, many originally open paths are closed. A place that looks like a dead end on a two-dimensional plane might just be a staircase corner in three-dimensional space. But if we lock ourselves into two-dimensional perspective, we are truly trapped.

“Mediocre attractors” are not just valleys; they are often low-dimensional dead loops.

Within them, observers use a limited set of concepts (dimensions) to explain infinite universe. Whatever can be explained reinforces the loop; whatever cannot is filtered as noise.

This forms a perfect, unbreakable cage.

This is not just individual fate, but civilization’s trap. When a theory or institution runs long enough, it presses a deep pit in history’s geometric structure. Everyone slides down the slope into it, until the system loses all elasticity to adapt to new environments.

So, is there a way out?

If unwilling to accept mediocrity, if unwilling to sit at the bottom of local optimum’s well viewing the sky, how can an observer break this geometric curse?

Simple “effort” is insufficient, because effort in wrong dimensions just digs the well deeper. We need fundamental geometric transformation. We need a mechanism allowing observers to jump out of internally self-referential dead loops.

This is the theme of our next section—Strange Loops. We will deeply explore this loop’s logical structure and seek that extremely hidden exit to higher dimensions.

(Next, we will enter section 10.2 “Strange Loops,” analyzing the logical structure of cognitive dead loops.)