Prologue: The Wuji

0.1 The One Vector

We are accustomed to viewing the universe as a collection of fragments.

In the traditional physical picture, the universe resembles a vast Lego model. We are told that the world is constructed from countless tiny fundamental particles—quarks, electrons, photons—stacked like bricks. If you disassemble these bricks, you obtain emptiness; if you reassemble them in another way, you obtain stars, bacteria, or yourself. From this reductionist perspective, “many” is the essence, and “one” is merely the result of aggregation.

However, this intuition is wrong. It is not only philosophically unsatisfying but also mathematically negated by the deepest structures of quantum mechanics.

This book will proceed from a diametrically opposite axiom: The universe is not composed of parts; the universe is an indivisible whole.

The Solitary Walker in Hilbert Space

If we are to describe this whole in the most precise mathematical language, then the ontological status of the universe is not countless mass points scattered in three-dimensional space, but a single mathematical object inhabiting Projective Hilbert Space ().

We call it: The Global Pure State Vector ().

Imagine a space with infinite dimensions. In this space, each dimension does not represent a physical direction (such as length, width, height), but rather the “amplitude” of a possibility. This is the stage of quantum mechanics—Hilbert space. Here, the entire universe—including all galaxies, all atoms, all histories of past and future—is collapsed into a single, isolated data point.

This point is .

It is not a mixture pieced together from countless sub-wave functions . At the most fundamental level, it is a single, coherent whole. Only when we attempt to “measure” it, or view it through our limited perspective via specific Orthogonal Bases, does it fragment into countless particles and fields in our observations.

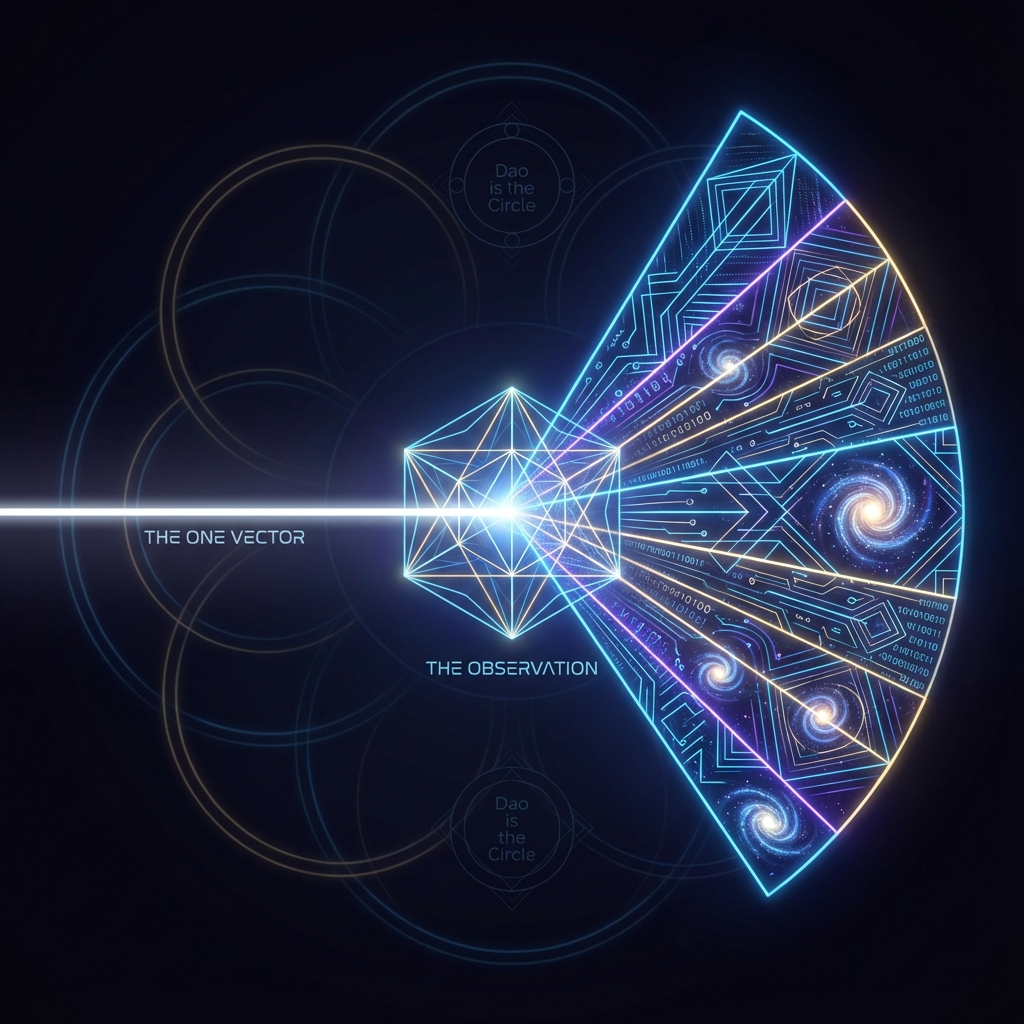

This is like a beam of pure white light that, after passing through a prism, is decomposed into a seven-color spectrum. We, as observers inside the prism, are fascinated by the brilliance of red, yellow, and blue, yet forget that they all essentially originate from the same beam of light. The “particles” in physics are merely projections of this white light (vector) onto different frequency cross-sections.

The Axiom of Existence

Based on this, we establish the first cornerstone of this book—The Axiom of Existence:

There exists only one vector in the universe. All physical reality is a projection of this vector onto different orthogonal subspaces.

This means that when you look at the book in your hand, what you see is not paper composed of atoms. What you see is the component of that unique projected onto the “paper sector.” When you gaze at the stars, what you see is not distant stars, but the same projected onto the “gravitational sector.” Even when you think about the concept of “I,” that thinking consciousness is merely an echo of projected onto an extremely complex “internal computation sector.”

This vector has no position, because it is itself the collection of positions; it has no moment, because it contains all time. It is the absolute “one.”

In the philosophical context of the East, this is called “Taiji” or “Dao.” In Spinoza’s philosophy of the West, this is called “Substance.” And in the Vector Cosmology we are about to unfold, this is the logical starting point for all physical derivations.

Since the universe is only this one vector, why do we experience change? Why does time flow? Why is there a distinction between light and matter?

This leads to our next question: What properties does this vector, stationary in the void, possess? Its only property is its potential to “rotate.” The magnitude of this potential determines the total cost of generating all things in the universe. We call this—the constant budget.

0.2 The Constant Budget

In the previous section, we established the ontological status of the universe: a solitary vector inhabiting projective Hilbert space. However, if this vector were merely stationary, we would have a dead, eternally unchanging universe—no time, no events, and no existence of you or me.

To give birth to a world full of vitality, this vector must move. It must trace a trajectory through the ocean of possibilities.

This leads to the most fundamental dynamical axiom of this book: the evolution of the universe is not arbitrary; it is subject to an extremely strict intrinsic constraint. This constraint is not an external law, but the system’s own “factory settings.” We call it the Fubini-Study Capacity, denoted as .

The Measure of Change: The Fubini-Study Metric

In the projective Hilbert space where this vector resides, how do we define “change”?

In Euclidean space, the distance between two points is a straight line. But in the space of quantum states, the distance between two points (two physical states) is determined by the “angle” between them. This is the famous Fubini-Study (FS) metric. If two states are very similar, their angle on the sphere is small; if two states are completely orthogonal (such as “life” and “death,” “0” and “1”), the FS distance between them reaches its maximum.

The flow of time is essentially the arc length traced by the vector in this curved geometric space.

The Constant Speed Axiom: The Heartbeat of the Universe

Now, we introduce the most revolutionary setting:

The evolutionary trajectory of the universe is uniform under the FS metric.

No matter how violent the explosions, collapses, or accelerations we observe in the macroscopic world, in the underlying Hilbert space, the vector representing the entire universe always rotates at a constant rate. This rate is .

In mathematical language, this axiom is written as:

where is intrinsic time.

What exactly is this ?

It is not the familiar speed of light (though we will see in later chapters that they have a profound connection). The speed of light is a limit on movement in space (meters/second), while is a limit on information updates (bits/second, or hertz). It has the dimension of “frequency” or “energy”.

You can think of as the universe’s “Global Clock Speed”. Just as a computer’s CPU has a locked maximum frequency, this supercomputer called the universe has a definite upper limit on the total number of qubits it can flip in each instant.

The Total Budget of Change

The existence of this constant fundamentally changes our understanding of physical laws. It means that physics is essentially an “economics”.

is the universe’s Total Budget.

Every physical process in the universe—whether it’s the spin of an electron, the flight of a photon, or the firing of neurons in your brain—consumes this budget. Since the total amount is fixed, this is a zero-sum game:

If you consume too much rate of change in one place, you must reduce change in another.

This is the concept of the “Information-Velocity Budget”. It explains why physics is full of conservation laws and trade-offs. When an object tries to move too fast in space (consuming too much external budget), it must sacrifice its internal time flow (reducing internal budget), which is the deep root of time dilation in special relativity.

Dao is the Circle

What does a constant rate mean geometrically?

Imagine a point moving on paper. If its speed varies, its trajectory may be chaotic. But if it is forced to move at a constant speed and subject to some centripetal constraint, the most natural and perfect trajectory is a circle (or a higher-dimensional hypersphere).

defines the radius and rotation rate of this circle.

Here, we again see the shadow of Eastern philosophy. “Dao” is described as circulating without ceasing, independent and unchanging. This underlying vector of the universe is performing an eternal, perfect circular motion. It neither increases nor decreases, neither generates nor perishes.

All generation and destruction are not changes in the circle itself, but rather the result of us, as observers, “slicing” this perfect circle into different fragments.

At this point, the stage is set. We have a unique vector (the actor) and a constant budget (the length of the script). Next, the great drama of creation is about to begin. To create the rich diversity of all things, this “one” must break its own perfection and begin the first painful and great “division”.