8.1 The Weber-Fechner Law

“Why does lighting a candle in the dark feel so bright, while lighting the same candle in sunlight is almost invisible? Because your eyes are not photon counters; your eyes are logarithmic calculators. To survive in a universe where the dynamic range spans dozens of orders of magnitude, your nervous system must learn to lie—it disguises crazy multiples as gentle additions.”

The Nonlinearity of Sensation

19th-century psychophysicists Ernst Weber and Gustav Fechner discovered a puzzling phenomenon: human perception of stimulus intensity is not linear.

-

If you hold a 100-gram weight, adding 10 grams makes you feel heavier.

-

But if you hold a 1000-gram weight, adding 10 grams makes no difference. You need to add 100 grams to produce the same “feeling of heaviness.”

This means: The increment of sensation () is proportional to the relative increment of stimulus ().

Integrating this differential equation, we obtain the famous logarithmic formula:

where is the subjective sensation magnitude and is the physical stimulus intensity.

This formula tells us: Every time the external world increases by one “order of magnitude” (multiplication), our internal sensation only increases by one “step” (addition).

-

Sound decibels (dB) are logarithmic.

-

Stellar magnitudes are logarithmic.

-

Musical pitch octaves are logarithmic (frequency doubles, but perception only rises by one octave).

The Dynamic Range Matching Problem

Why did evolution choose this strange way of perception? Why not let us directly see the real photon count?

The answer lies in the finiteness of FS capacity ().

In the first book, we established that any physical system—including our neurons—has a maximum information processing bandwidth. Neuronal firing frequencies have an upper limit (approximately 100-1000 Hz). This means our “internal display” has only limited grayscale levels (e.g., 0 to 255).

However, the external universe is an exponential world driven by .

-

Sound intensity range: from a mosquito’s buzz to a jet engine, spanning times the energy difference.

-

Light intensity range: from starlight to noon sun, spanning times the photon flux difference.

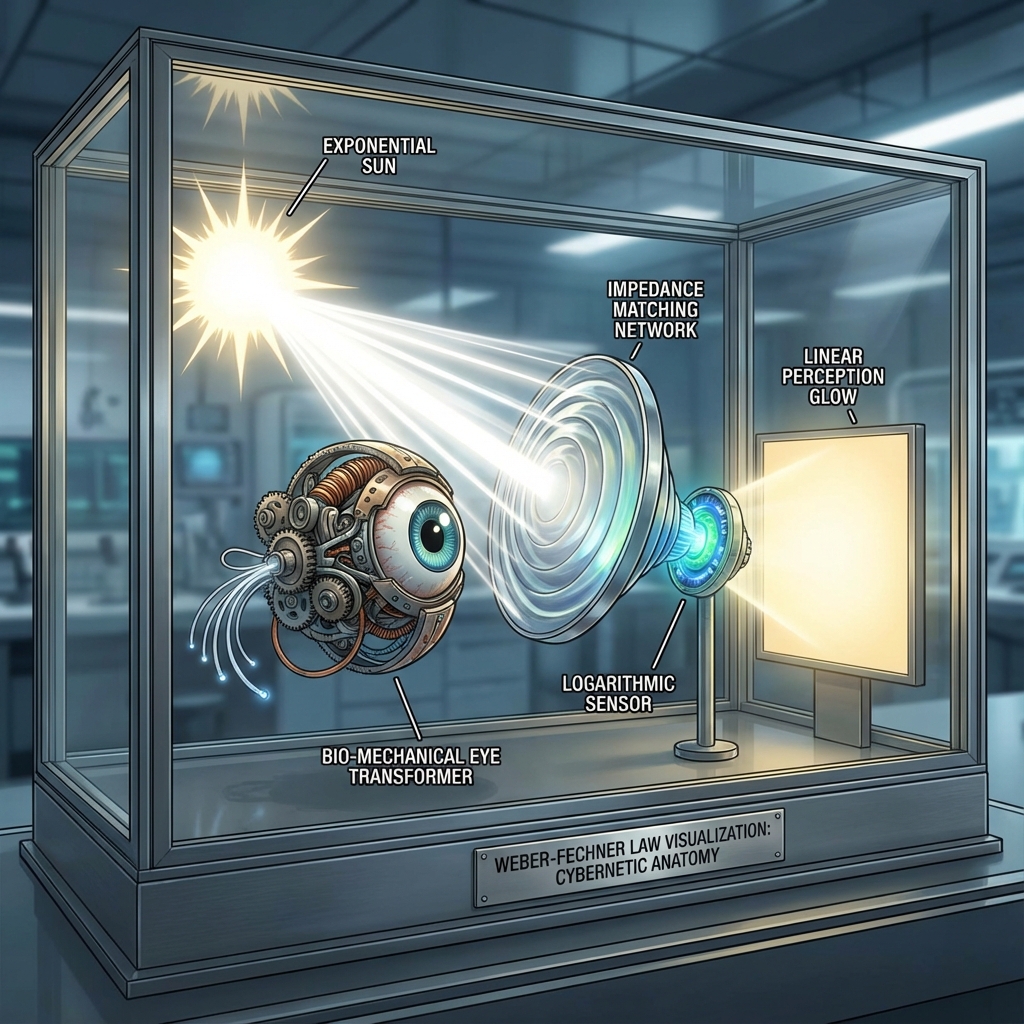

This is an Impedance Matching nightmare.

If our senses were linear ():

-

If we were sensitive enough to see dark details, we would instantly “overload” during the day, neurons would overload, and we would go blind.

-

If we were adapted to strong light, we would become blind at night, completely unable to see weak photons.

Dimensional Reduction Projection in Geometry

To solve this problem, life was forced to hardcode the (logarithm) algorithm at the hardware level.

In the geometric language of Vector Cosmology, this corresponds to the inverse mapping from tangent space to manifold.

-

External input (): Vectors in Hilbert space with exponentially growing modulus (driven by ).

-

Internal perception (): Linear potential changes that neurons can carry (limited by ).

The sensory system of living organisms is essentially an Analog Logarithmic Converter.

The chemical reaction dynamics on the retina and the basilar membrane resonance structure in the cochlea cleverly utilize nonlinear physical effects to achieve the operation .

Through this operation, we compress the universe’s violent, multi-order-of-magnitude energy tsunami into a gentle linear stream that we can safely process.

Conclusion: We Are Logarithmic Functions

The Weber-Fechner Law is not just about sensation; it is about “existence”.

It proves our deep mathematical relationship with the universe:

The universe is an exponential expander; we are logarithmic convergers.

The reason we feel the world is stable, predictable, and linear is not because the world itself is so. Rather, our senses are like a pair of “logarithmic glasses” that filter out the exponential madness at the bottom of the universe.

We live in an illusion tamed by .

But this is a merciful illusion. It is precisely because of this filter that we can maintain sanity, experience life, and produce the tranquility of “linear time” in the exponential explosion of .

Since our senses are logarithmic, is the core operating logic of the brain that processes these sensory data—cognition and thinking—also built on some geometric mapping?

This leads to the theme of the next section: The Geometry of Cognition. We will see that not only sensation, but even our “understanding” itself is a projection operation that forcibly flattens high-dimensional manifolds onto low-dimensional tangent planes.