2.2 The Art of Projection

If the universe’s ontology is truly that “final object” silently rotating in Hilbert Space, then the question arises: Why have we never seen it?

We have never felt ourselves living in an infinite-dimensional vector ocean, nor have we directly experienced that pure “becoming.” Instead, we see three-dimensional space, feel flowing time, and touch solid objects. The world in our eyes is full of concrete limitations: objects cannot be both here and there, time cannot return once it has passed.

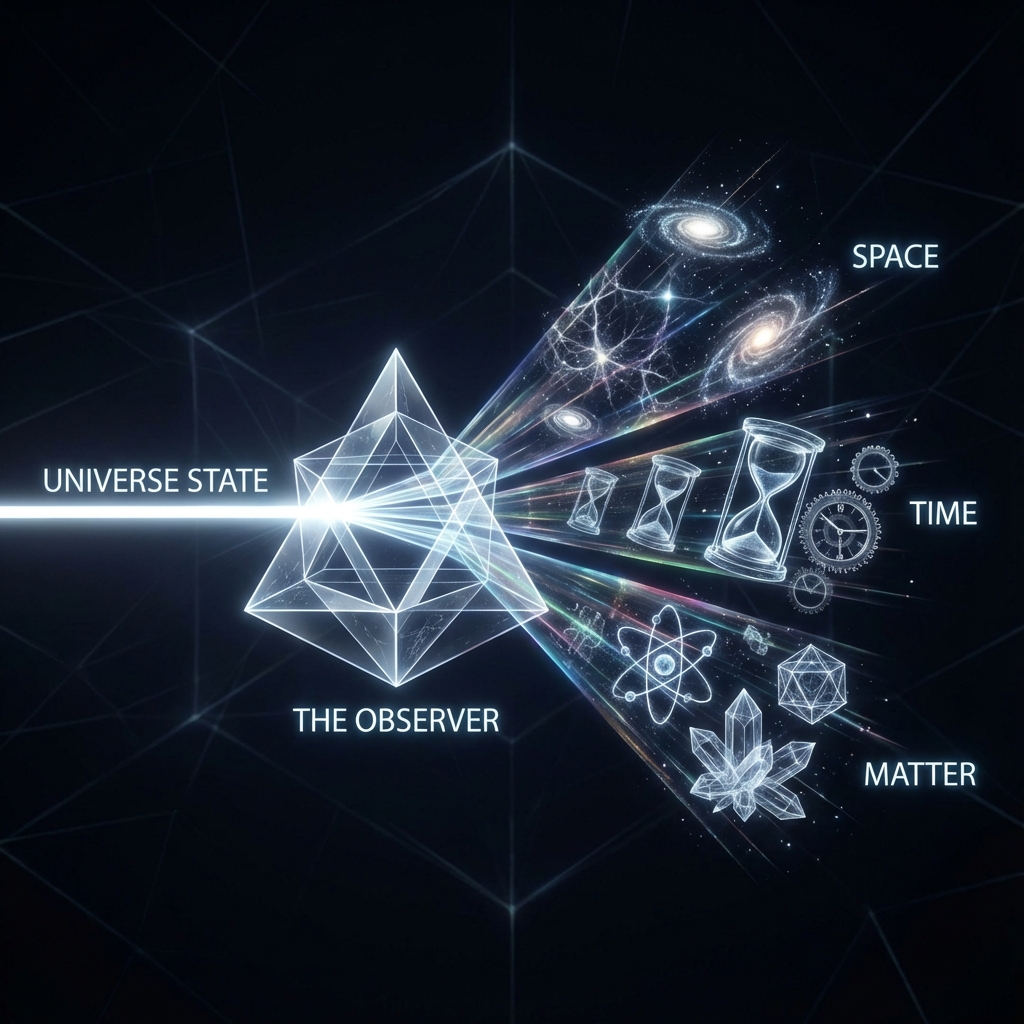

This enormous contrast stems from an act we perform every moment yet never notice—projection (Projection).

Plato’s Cave 2.0

Two thousand years ago, the philosopher Plato told a parable: A group of prisoners were trapped in a cave, facing away from the entrance. They could not see the real world outside, only the shadows projected onto the wall. For these prisoners, shadows were the only reality.

In this parable, Plato touched upon a profound physical truth, but he only got half of it right. In our geometric reconstruction, the universe is not the world “outside”; the universe is that high-dimensional ontology. And we, as observers, are not merely passive spectators; we are that projector.

In Hilbert Space, the universe’s state vector contains extremely rich information—it is holographic, it is infinite-dimensional. But as physical observers (whether human, detector, or a simple particle), our “bandwidth” is extremely limited. We cannot simultaneously process all the universe’s information.

To understand the universe, we must simplify it.

Mathematically, this is called “dimensional reduction.” Like flattening a three-dimensional globe into a two-dimensional map, you lose some truth (such as Greenland’s distortion), but you gain a usable coordinate system.

This is the physical essence of observers as projection operators.

When we observe the universe, we are actually cutting a low-dimensional “slice” in Hilbert Space. We project that rotating cosmic arrow onto a few specific axes we have chosen—such as the “position” axis, the “momentum” axis, the “time” axis.

-

The originally unified evolution rate is projected onto the spatial axis, becoming the velocity we see.

-

Projected onto the internal degrees of freedom axis, becoming the mass we measure.

-

Projected onto the causal chain, becoming the time we perceive.

What we call “physical reality” is actually the sum of these projections. Just as a photograph is only a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional world, the spacetime we inhabit is also a four-dimensional projection of high-dimensional Hilbert Space.

The Cost of Forgetting

Projection is an art, but it is also a form of forgetting.

When you project a three-dimensional object onto a two-dimensional paper surface, you inevitably lose depth information. Similarly, when we project the universe’s ontology into the physical world, we lose vast amounts of information. In Category Theory—an advanced language for studying mappings between mathematical structures—observers are described as a forgetful functor (Forgetful Functor).

This name sounds poetic and cruel. It means: To have a clear physical world, we must forget the vast majority of the universe’s truth.

The “wave function collapse” in quantum mechanics is precisely this violent manifestation of “forgetting.” When we make a measurement, we forcibly require the universe to choose only one specific projection (such as “electron here”) from its originally superposition state containing all possibilities. Where did the other possibilities go? They are “filtered” out by the observer’s limited bandwidth, or orthogonalized into dimensions we cannot see.

But this does not mean the physical laws we see are false. On the contrary, physical laws are the topological structures preserved during projection.

Just as no matter how you rotate a donut, its projection will always somehow hint at the existence of that “hole,” certain deep invariants in the universe’s ontology (such as the total evolution rate ) become those unbreakable physical constants in our world after projection.

Metaphor as Truth

In this framework, we need to re-understand what “truth” is.

Traditional science tells us that truth is a statement about “what matter is.” But here, truth is a statement about how structures map.

We will frequently use “metaphors” (Metaphor) in this book. We say “mass is a knot in time,” we say “light is the destitute.” Please do not treat these merely as literary rhetoric.

In the context of geometric reconstruction, metaphor is a strict mathematical mapping.

When we map the geometric structure of Hilbert Space (source category) to the physical phenomena of spacetime (target category), if this mapping preserves all mathematical structures (such as isomorphisms or functors), then this “metaphor” is physical truth.

-

When this mapping preserves the Pythagorean theorem structure, we obtain Special Relativity.

-

When this mapping preserves unitary group symmetry, we obtain the Standard Model.

-

When this mapping preserves the causal propagation limit of information, we obtain the speed of light limit.

Therefore, observers are not only prisms but also translators. We use our limited sensory language to translate that cosmic scripture written in infinite-dimensional language. Although translation always accompanies information loss (Traduttore, traditore), it is precisely this translation that creates the magnificent poem we call “reality.”

Now, we understand the essence of projection. But to truly read this book, we need a dictionary. We need to know which geometric symbol corresponds to which physical phenomenon.

This is our Rosetta Stone.

(Next, we will enter section 2.3 “The Rosetta Stone,” where we will present a clear comparison table showing how to translate difficult-to-calculate physical problems into simple geometric resource problems.)