2.3 The Interface Protocol (Stinespring-Turing Isomorphism)

(The Interface Protocol - Stinespring-Turing Isomorphism)

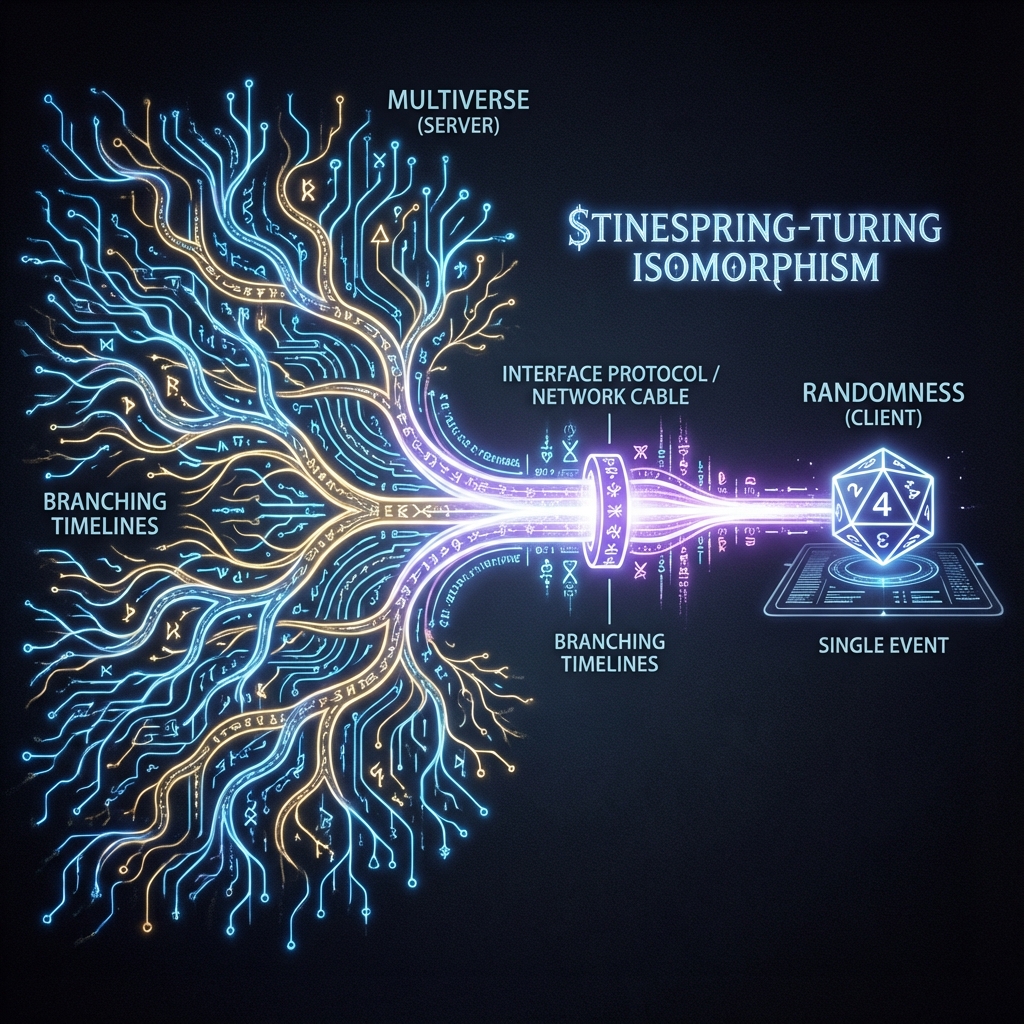

“Randomness is the shadow cast beyond the field of view. So-called ‘collapse’ is nothing but packet loss and compression when huge server data streams squeeze through your thin network cable. This section will prove that ‘multiverse’ and ‘free will’ are actually the same thing, just viewed from the server or from the client.”

In sections 2.1 and 2.2, we established two models:

- Server model: Omniscient, multithreaded, contains all histories.

- Client model: Single-threaded, can only see one result, full of randomness.

Physics has argued for a hundred years, some saying the world is deterministic (Einstein), some saying it’s random (Bohr). This is actually because they confused server logic with client logic.

In this section, we will prove the core theorem of the entire book—Stinespring-Turing Isomorphism Theorem. Translated: Perfect seamless client synchronization protocol.

We will prove that for you, a player who can only stare at the screen, you can never tell whether you’re living in a deterministic multiverse or a random single-player game.

2.3.1 Theorem Statement: Computational Indistinguishability

Theorem 2.3.1 (Blizzard Protocol Isomorphism)

For any game process, the following two interpretations are mathematically completely equivalent:

-

Server perspective (global unitarity): The entire Azeroth is a huge, precise machine with no randomness. All places that generate random numbers (like rolling dice) actually rolled not only 100, but also 1-99, just in different parallel planes.

-

Client perspective (interactive randomness): The server not only sends you data, but also sends you a random seed. Each roll, your client calculates a unique result based on this seed and your input (click timing).

Physical corollary:

As long as you cannot hack into Blizzard’s server room to check backend data (i.e., cannot access the environment beyond the horizon), you can never distinguish these two situations through experiments.

What you think is free choice may be parallel universe branches; what you think is random fate may be high-dimensional data projection.

2.3.2 Forward Proof: From Parallel Worlds to RNG

Let’s first see how the server’s determinism becomes randomness in your eyes.

Suppose the server calculates an attack judgment. At this moment, the server produces a superposition state:

- State A: Crit (50%)

- State B: Miss (50%)

These two states coexist in server memory. But your network cable (bandwidth) can only transmit one state’s data packet at a time.

So, the server throws a dice based on the weights (probabilities) of these two states and decides to send you the “crit” data packet.

To you, you see a crit. You think this is “random” luck. But actually on the server side, that “miss” history didn’t disappear; it just wasn’t sent to you (or was sent to another you in a parallel universe).

Conclusion: The multiverse structure, in the client’s view, “collapses” into a random number generator (RNG).

2.3.3 Reverse Proof: From RNG to Parallel Worlds

Conversely, any seemingly random single-player game can be “whitewashed” into a grand server event.

Imagine you’re playing a pure single-player game. Monster drops are completely random. This is mathematically called “mixed state evolution.”

The famous Stinespring Dilation Theorem tells us: Any process containing randomness can be seen as part of a larger, randomness-free process.

We can imagine an invisible “environment server.” Whenever your single-player game generates a random number, your computer actually entangles with this environment server.

This equation tells us: Any random event corresponds to some information record at a deeper level.

Physical meaning:

This tells us that “free will” does not violate physical laws. It merely means every choice you make leaves an indelible log record in the universe’s backend. The client’s input command is the server’s environment variable.

2.3.4 Consequences of Holographic Equivalence

This theorem completely reconstructs our understanding of “reality,” establishing the Holographic Computational Equivalence Principle:

-

Duality of interpretation:

- Many-worlds interpretation is the truth for server administrators.

- Copenhagen interpretation is the truth for ordinary players.

- They are not opposed; they are just perspective differences caused by different user permissions.

-

Graphics card as oracle:

- That mysterious “input source” in the client model is physically your horizon. The horizon shields the server’s complexity, converting those entanglement relationships that would explode your graphics card into simple random noise.

-

Computational conservation:

- The server consumes space (storing all parallel universes).

- The client consumes time (real-time calculating current history).

- Trading time for space: The universe makes you feel it’s “single history” because you, as a player, don’t have enough memory. You can’t load the entire game, so you can only endure “time passage”—that is, frame-by-frame data loading.

Thus concludes Volume I “Principles of the Game Engine.” We proved that Azeroth is a finite, computable system, and explained why you feel you’re playing a real-time game.

In the next Volume II, we will leave the boring code layer and enter the real Azeroth world—to see how the speed of light (network latency) and gravity (server load) affect your gaming experience.